Aïcha Snoussi: Queer Tunisian Surrealism

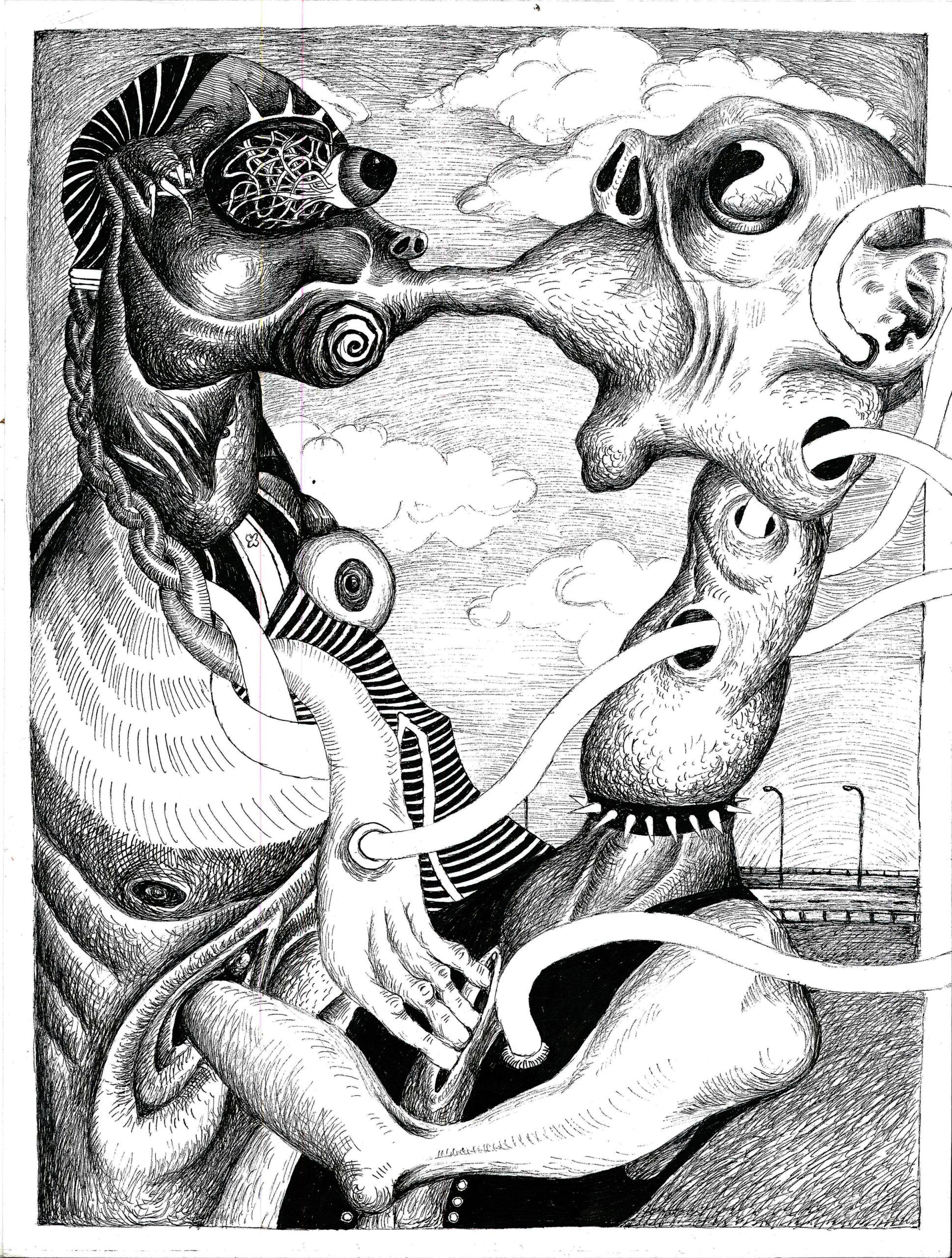

Aïcha Snoussi, a queer-identified Tunisian artist, was born 1989 in Tunis and lives and works between Tunis and Paris. Her artistic practice engages with questions of the body, sex practices of pain and pleasure, and systems of knowledge, and her artworks often sit at the intersection of boundaries between animal, human, and machine, problematizing several particular dichotomies, namely, human/animal, animal/machine, organic/inorganic, and male/female. Snoussi’s untitled graffiti work from 2016, Le livre de anomalies (The book of anomalies, 2017), and Bugs (Anticodexx, 2017) each play with bodily plurality through the combination of animal, human, and machine. In these three works, Snoussi depicts uncanny bodies drawn in notebooks or painted on a building. The figures are also queer. As David J. Getsy summarizes, “the defining trait of ‘queer’ is its rejection of attempts to enforce (or value) normalcy,” namely in regards to sexuality. The artworks subvert categories upon which authority often relies, such as genital sex and gender, through the deployment of queer as an ontology in which works produced by a queer-identified person embody that artist’s lived realities.

Snoussi’s artworks also engage queerness as a methodology, which can be thought of as an unfixed process; not necessarily one of exclusively sexual identification or activity, but of actions, interpretations, and disruptions. Queer methodology can also be a method of creating space in which “queerness and the practice of queer politics [can create] a space in opposition to dominant norms, a space where transformational political work can begin.” Snoussi’s artworks create such spaces by presenting alternatives to normative bodies and sexualities. I will use ‘queer methodology’ when deploying queer in this way so as to differentiate the two usages.

The artworks discussed herein are able to be read, in one way, as queering Tunisian social normalcy and state expectations, through the recuperation of specific socio-material existences; specifically, the depiction of bodies that disrupt not only the bounds of normatively gendered and sexed bodies, but that also trouble the borders between human, animal, and machine. The chimeras found in Snoussi’s artworks are such bodies.

As boundary blurring entities, chimeras disrupt binaries and their corresponding hierarchies. But chimeras also embody a fundamental multiplicity. In the figure of the chimera, one is two or more (genetically distinct organisms), or rather, not one or two, but plural. The cyborg embodies a similar status; for the cyborg, one is plural. The figure of the cyborg, as a merger of juxtapositions between machine, animal, and human, is a type of chimera. The cyborg further introduces the possibility of “man-made” or rather, “man-modified” as an interlocutor of the human. Donna Haraway contends that, “The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centres structuring any possibility of historical transformation.” For Haraway’s cyborg “The self is the One who is not dominated…to be One is to be autonomous, to be powerful, to be God; but to be One is to be an illusion, and is to be involved in a dialectic of apocalypse with the other. Yet to be other is to be multiple, without clear boundary, frayed, insubstantial. One is too few, but two are too many.” Two are too many because two is made from one plus one. With two, there are merely two ones. Two does not mean a new or different structure. Two therefore reinscribes one, entering into a duality that functions not unlike a binary, here formed as singular/plural. The figures of the chimera, and in a different but parallel vein, the cyborg, allow bodies and subjects to be conceived of as possibilities besides one or two. I will use the term “plurality.”

Bodies are a major foundational component of social authorities because they often bear out the social meanings of the state’s mandates. The material and social destabilization of bodies can thus disrupt social authorities. As Heather Love describes, “In its embrace of a politics of stigma and its reliance on a general category of social marginality, queer theory borrowed its account of difference from deviance studies. As is well known, queer sidesteps traditional identity categories such as gay, lesbian, and bisexual in favor of a more general category of social marginality.” Snoussi’s artworks sidestep traditional categories of sexual identity and sex acts to demonstrate a merger of queer and surrealist art in Tunisia that draws on the uncanny and surrealist aesthetic traditions of artists such as Aicha Filali, Meriem Bouderbala, Ymène Chetouane, and Houda Ghorbel, but that brings an explicitly queer perspective to bear on a critique of post-revolution Tunisian authority through the figure of the chimera.

Aïcha Snoussi, untitled graffiti work (2016)

In 2016, as part of the Chouftouhonna feminist art festival held in Tunis, Tunisia, Aïcha Snoussi painted a site-specific graffiti work on the exterior of an old one-screen cinema. The enormous, tentacled creature, not quite an octopus, but also not closely resembling any other animal, human, or machine, dominated the steps and columns of the porte-cochère. Its white tentacles, outlined and shaded with black and gray, wound around columns and climbed up walls, overlapping its other features: a network of pipes or tubes. These tubes, evidently part of the figure’s body, were painted with the same colors and on the same scale as the tentacles. Yet, they were much more machine-oriented than the seemingly organic curves of the tentacles. Any part of the creature that could be said to resemble a head was not apparent. The denial of a central aspect to the figure invites the possibility that the building itself is the creature, and its appendages merely extend outward uncontained by the bulk of its center mass. This possibility is supported by the presence of the pipes, which remind that the creature has some relationship with man-made elements.

The creature evokes surrealism in its uncanny, chimeric composition. Sigmund Freud attests that “the ‘uncanny’…undoubtedly belongs to all that is terrible – to all that arouses dread and creeping horror… [we can] distinguish as ‘uncanny’ certain things within the boundaries of what is ‘fearful.’” The chimera, a figure that exists only in bodily pluralities, also evokes horror. Chimera has two modern connotations that, while different, are not unrelated. Commonly, a chimera is thought of as a creature from Greek mythology. It is often depicted as a winged hybrid creature: the ‘front’ is made up of several heads, often including those of a lion and a goat, and the ‘rear’ is the head of a snake or a dragon. But in molecular biology, specifically embryology, a chimera describes a cluster of cells made up of cells from different individuals. Scientifically, to be an individual means to be genetically distinct, while not precluding that individuals can be grouped as belonging to the same species, for example. In a chimera, as in Snoussi’s artworks, bodily plurality can be foregrounded as a method by which to disrupt the singular sexed body that constitutes systems of sexual fixity, normative gender, and family structures that uphold the state.

Bodily plurality such as in Snoussi’s graffiti disturbs binaries. Binaries are strict methods of organizing two terms in relation to one another so that the concepts are proposed as opposites. By setting two concepts in opposition, binaries necessitate that each concept is defined on the terms of the other. Bodily plurality thus disrupts the singular-sexed body that is so often used as a social adherent between a monogamously mating pair of humans, and thus further deployed to build gender, society, and the nation, which are in turn utilized by social authorities. The unambiguously unitarily sexed body is, after all, thought of as universal and is rarely bound up in plurality.

The female body is a particularly contentious site in Tunisia where it is in a continually constituted by its relationship to male family members. Tunisian artist Aicha Filali expands upon the position of the female body in a heteropatriarchal society, specifically in Tunisia, stating, “a woman’s body does not belong to her. It belongs to her father, her brother, her husband, but not to her. It is an object of lust. I went to Senegal, the woman’s body wasn’t a problem at all. I think [Tunisia’s] problem rests in a misunderstanding of Islam: ‘retrograde’ Islam.” Filali indicates that a woman’s body has two states, both which are in relationship with men who control it: in marriage and in preparation for marriage. In mentioning the cultural embeddedness of Tunisian Islam, she also describes how the extra-state, or cultural norms that pre-date the nation-state, is intertwined in social authority.

The chimera is constituted through bodily plurality; its state of being multiple functions outside of the one/two structure. Chimeras are apt descriptors for the bodies in Snoussi’s works in which, outside of the science lab, chimeras are commonly conceived of as mythological hybrids. This classification presumes that the divide between fantasy and reality is reliable. But in surrealism, the separation of fantasy and reality is slippery and the boundary between the two often exists through policing by social authority.

In Snoussi’s untitled graffiti work, the boundaries of reality and fantasy can be understood as the contrast of state and social proscriptions for women and queer people, particularly queer women. With Snoussi’s creation of improbable, queer beings that inhabit liminal spaces of non-binary genders and sexualities, she proposes such spaces within the physical bounds of a nation-state that denies LGBTQ people sexual and bodily autonomy through imprisonment and social prescriptions that fail to recognize queer women’s relationships as extant.

While Tunisian women enjoy professional statuses such as lawyers and doctors, they often remain caught between the state’s allowances and familial requirements. Sexual relationships are one prime indicator of this contrast. As Pinar Ilkkaracan has argued, Islam is encouraging of sexuality for heterosexual men, but active female sexuality is repressed. Queer and lesbian relationships between women are often erased due to their non-existent relationship with penile penetration. Fatima Mernissi articulates how many Islamic societies conceptualize and respond to active female sexuality, noting the irony in that the that need to surveille and restrict women’s movements would indicate that these societies are threatened by the possibility of women’s active sexuality, yet the social conception of women’s sexuality is as passive and receptive. Queer sexual relationships are likewise deemed incompatible with societies that rely heavily on strict gender divisions, based in sexed bodies and highly gendered familial relationships.

Roddey Reid critiques the normative family by proposing that the constitution of the human in no uncertain terms begets the constitution of the nuclear family, and likewise, that nonnormative human bodies (i.e. less than human) disrupt and threaten the family. Also, when the family is disrupted, humanity itself is threatened. This occurs because humanity is often implicitly understood in terms of the nuclear family. Likewise, rhetoric of the family and ideas about how humans should group and interact socially and sexually are often used to humanize individuals and groups. I build upon Reid’s claim to assert that while there is no implicit relationship between genitals, the singular-sexed body, the family, and social authority, there is a constructed relationship. The singular-sexed body is constituted through clear demarcation of human genitalia as falling unambiguously into the categories of penis (male) and vulva (female). Genitalia is mapped onto sex, which further, is commonly mapped onto gender so that penis=male=man and vulva=female=woman. Following this mapping, normative, nuclear family structure involves one man with a penis and one woman with a vulva who produce a culturally acceptable number of offspring. When the body is sexed as male or female, plurality ends. Plurality could be recuperated, however, through the figures of the chimera and the cyborg. Cyborg and chimera bodies recover the potential for genital, sexual, and gender plurality, upending the normative constitution of the family.

Such socio-material categories as human and machine are dependent upon constructions of sex and the singular body. By demonstrating the fictitiousness of human/animal and animal/machine divisions, and the one/two and singular-sexed body, for example, the chimera and the cyborg also help destabilize the fundamental social binaries of sex and gender. The chimera and the cyborg further function as plural bodies, negating the very possibility of a body entering into a binary relationship. Thus, the figures of the cyborg and the chimera reject mandates of gender, sex, family, and other expectations set forth by social authority. Chimeras and cyborgs are particular examples of queer materiality in which the body and its sex, including potential sex acts that beget offspring to constitute the family, are disrupted.

As an octopus, Snoussi’s graffiti figure complicates non-normative possibilities of (heteronormative) sex. Male octopuses have a specialized arm, a hectocotylus, which they insert into the female’s mantle in order to deposit sperm. The male does this at the risk of being cannibalized. In Snoussi’s octopus, any of the arms or pipes could be a sexual organ. Octopuses have a central brain, like humans, but they also have a decentralized nervous system in the form of neural clusters in their tentacles. As Peter Godfrey-Smith explains, “vertebrate brains all have a common architecture. But when vertebrate brains are compared with octopus brains, all bets—or rather all mappings—are off. Octopuses have not even collected the majority of their neurons inside their brains; most of the neurons are in their arms.” The possibility arises that the third ‘penis’ arm of the male octopus also contains a neural cluster. In fact, some species of octopus can detach their sexual arm during or in advance of the sex act. The arm performs its sexual function while separated from the main body of the animal. Its neurons must have the capacity to act independently. The octopus’ body therefore presents the possibility that a sexual act can be extra-body in some way, or disengaged from the main brain.

One such social-sexual meaning in Tunisia that might be disrupted through the figure of the octopus is the stigmatization of male anal penetration. As in some other Middle Eastern and Asian cultural contexts, in Tunisia, the penis is the active agent of the sex act. The penis may penetrate a vagina or an anus, but remains coded as the masculine and heterosexual aspect of sex. However, to be penetrated, whether vaginally or anally, is to be equated with the feminine. Thus, men who ‘top’ are not socially considered gay, while men who ‘bottom’ are stigmatized as homosexual so that being penetrated is equated with being submissive and feminine.

The octopus provides space for this discussion through its acts of copulation, which are characterized by physical distance and the possibility of the female’s cannibalism of the male. Both of these characteristics confound the normative human sex act, even sex acts of same sex couples. Thus, the subversive potential of the octopus sex act lies not in a rejection of heteronormative sex, nor in a celebration of homosexual sex, but in the manifestation of another possibility altogether.

If octopus sex is queer, the octopus’ body is also queer by nature of the sex acts it engages in and through its material composition. Godfrey-Smith states that “[the octopus] has a body—but one that is protean, all possibility; it has none of the costs and gains of a constraining and action-guiding body. The octopus lives outside the usual body/brain divide.” The brain/body quandary of the octopus makes it a queer body indeed; a queer, chimeric body of possibility. Not only is the octopus an invertebrate, its neural development is, in some ways, more advanced than that of humans; its system is more complex, to the degree that scientists speculate that an octopus can use both its central brain and its arm neurons at the same time to perform different tasks, each acting independently of the other.

Like veins and arteries, pipes circulate fluids to different areas in Snoussi’s graffiti work. This creature that has both arteries and pipes, or perhaps arteries as pipes, mimics the interior structure of the building upon which it is painted.

The building, an old one-screen cinema that has been adapted into a dance and performance space, is located in the historical area of Carthage, northwest of Tunis’ city center, where the Phoenicians established colonies nearly 3000 years ago. The building has the capability for another kind of circulation as well: plumbing and electrical wiring. Perhaps for the creature, as for the building, the pipes perform integrated functions. They carry water, waste, electrical signals, cables, and, in the Internet age, information. The overlapping contexts of ancient Carthage, French imperialism, and modern Tunisian space present a queer temporality. The heterosexual, nuclear family as the default of social organization is disrupted by the extension and overlapping of times and spaces in which it cannot be stated as fact that this normative family structure was normative, or even extant. By this conceptualization, the festival itself is a queer temporality in that it prioritizes expressions of queerness and non-normativity in the otherwise hostile Tunisian landscape.

Snoussi’s octopus-like graffiti evokes the figure of the chimera through which bodily plurality can destabilize the singularly-sexed body. In Tunisia, the state relies upon such differentiated bodies in prescribing women’s roles in both public and private life. Social gender norms also contribute to the conceptualization of women’s sexuality as simultaneously passive and as a threat to the operation of normative, patriarchal society. Queer sexual relationships also threaten normative society, particularly the heteronormative, monogamous family, in that they do not replicate the penetration required to produce children. As a foundational component of society as well as the state, the family provides a structure for gendered relationships that are likewise relevant for the promotion of the state.

Anne Marie E. Butler.

In Unintelligible Bodies: Surrealism and Queerness in Contemporary Tunisian Women’s Art. State University of New York at Buffalo, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2019.