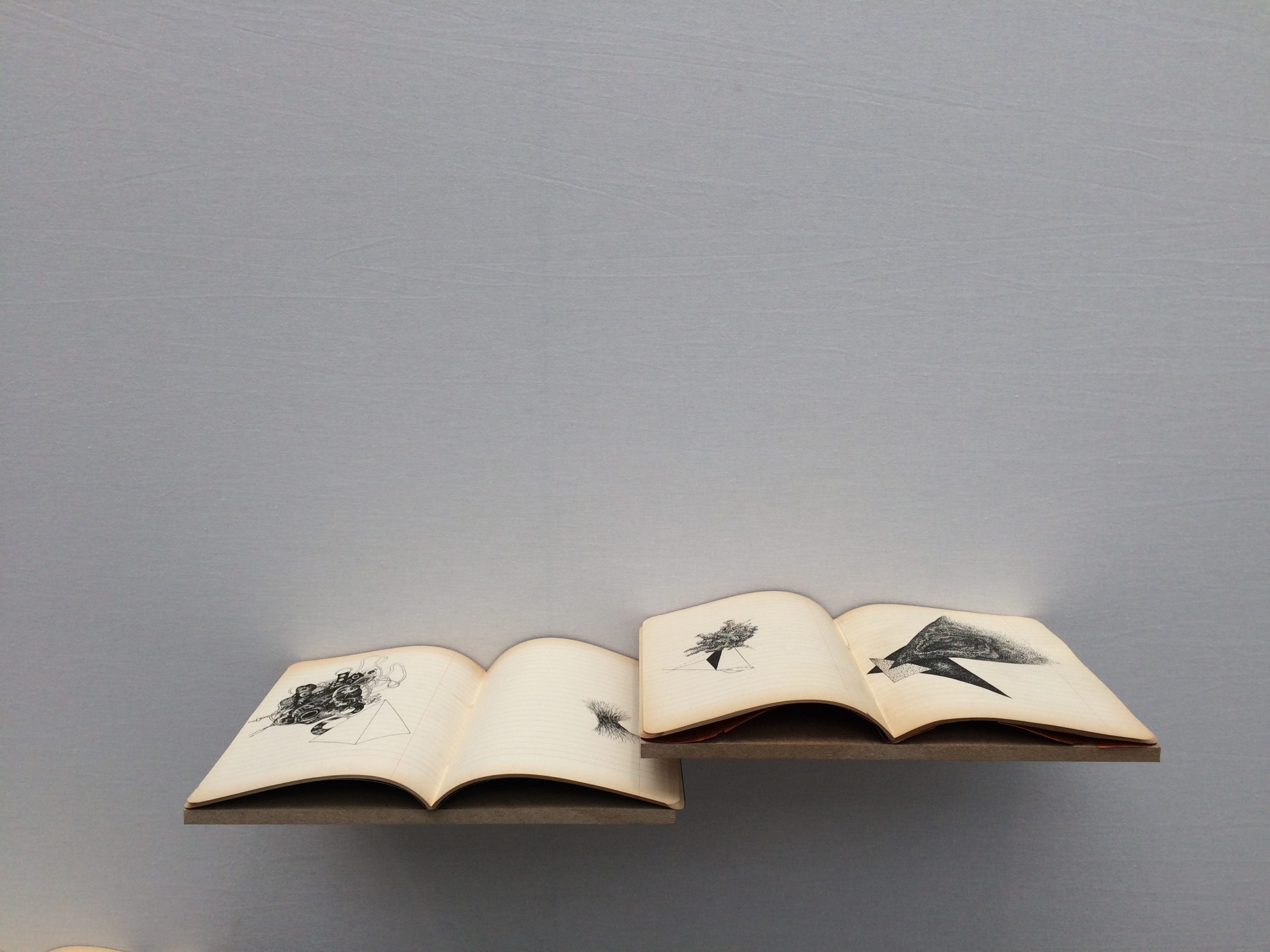

Aïcha Snoussi, Le livre des anomalies (The book of anomalies) (2017)

Aïcha Snoussi’s Le livre des anomalies (The book of anomalies) is an installation work composed of ink drawings in school notebooks. The book of anomalies is a new taxonomy of items that confronts typical categorical organization and accepted definitions. Because the entries are unfamiliar, and their relationship to one another remains open, they elude hierarchy and expose the social construction inherent in meaning making and ranking systems. The figures within the notebooks are not unlike the exquisite corpses of the European Surrealists in which multiple people contributed sections of a drawing to create an assemblage. Patricia Allmer notes that “the (ideological) status quo is challenged in surrealism, by seeking and teasing out the marvelous in the everyday – without departing from it, surrealist strategies reveal the everyday and familiar as marvelously unknown, different from itself, differing from what ideologies dictate it to be.” Snoussi’s drawings reference known shapes – animals, plants, and bodies – yet they are strangely rendered and configured in unexpected, and uncanny, combinations.

In this work, Snoussi presents vaginal imagery alongside drawings with phallic components. As Elizabeth Grosz contends, the history of philosophy has refused to recognize the “formative role [of the body] in the production of philosophical values – truth, knowledge, justice, etc. [and] above all… the role of the specific male body as the body productive of a certain kind of knowledge (objective, verifiable, casual, quantifiable) has never been theorized.” Snoussi’s prioritization of human female genitalia and of deviant sexuality in a nonsensical reference book centers the female body and queer sexuality as sites of knowledge production. Here, Snoussi’s genital forms become part of a new knowledge system, one that is inherently queer and that draws from, yet ultimately rejects, the male and science centered ways of knowing that dominate modern thought.

The title of the work indicates that the figures in the books are anomalies: of bodies, genitals, and sexual acts and relationships. As Eve Sedgwick contends, “That’s one of the things that ‘queer’ can refer to: the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically.”

Snoussi’s forms interrogate such monolithic significations, and with the word ‘anomalies,’ Snoussi evokes deviance and rejects the fetishization of the normal.

Anomalies are outliers, as are deviants. Sexual deviants, such as lesbians, gays, and bisexuals are those with sexual identities that exist in the margins of sexual hierarchy. Love summarizes the contemporary application of deviance, stating, “Queer critics [have] embraced deviance not as an inevitable counterpart to conforming behavior and an integral aspect of the social world, but rather as a challenge to the stability and coherence of that world.” The utility of embodied deviance and deviance in sexual practices and acts can therefore be as methods of destabilization to normalcy rather than states that can be assimilated.

In one pair of drawings, a polygonal shape appears like a vulva, opposite a bug-like creature with machine parts. On the vulval-shape, small lines, like hairs or folds, cover the outside areas and a small, bright point appears near the convergence of the two sides of the figure. By evoking human female genitalia, Snoussi’s imagery operates within, but in contrast to, power systems that determine hegemonic meanings. Human female genitals, coopted by patriarchal power structures, are made to symbolize a range of attributes related to the constructs of female, woman, femininity, gender, sex, sexuality, and so forth. Pierre Bourdieu discusses the gendered dimensions of genitalia, stating, “the social definition of the sex organs, far from being a simple recording of natural properties, directly offered to perception, is the product of a construction implying a series of oriented choices, or, more precisely, based on the accentuation of certain differences and the scotomization of certain similarities.”

The terms of female genitalia are set forth by a social agreement regarding first their purpose, procreation and pleasure for men, second their status as low, dirty, penetrable, vulnerable, and finally their aesthetics – beauty conditional upon cultural context and specific temporality, which increasingly in global beauty culture includes white, shaven, not menstruating, pre-pubescent appearing, labia minora laying neatly inside of labia majora, and clitoris not protruding from clitoral hood. Because a clearly sexed body is typically extrapolated to a clearly defined, singular gender, sexed bodies participate in producing the body as an entity without plurality. Snoussi’s uncanny genital shapes disturb such singularities.

The vulval figure is uncanny in several ways: it is disarticulated from a body, mediating its significance to the gendered body. A vulva that is uncoupled from the female body becomes at once both strange and familiar. As Whitney Chadwick contends, “In many cases Surrealism has provided the starting point for works that challenge existing representations of the female body as provisional and mutable, or at least initiating a shift away from the phallic organization of subjectivity.” Such surrealist, uncanny bodily arrangements as Snoussi’s vulval shapes work outside of normalcy. These forms often cut across the normative human or the body. Like Sedgwick, who delineates that the origins of the word queer (the Indo-European “twerkw” (across) and the German “quer” (transverse)) enable the term to cut across reductive conceptualizations of homosexuality, queer bodies might act at a “cross” angle to normative bodies. As J. Jack Halberstam and Ira Livingston contend, the “‘human body’ [is] a figure through which culture is oriented and processed.” Bodies and sexual parts that deny the ascription of sex and gender disturb such processes of orientation.

In the same detail image, a cord emerges from the vulvic area of the drawing. With a colorless segment near one end, the cord seems almost worm-like, while at the other end, something akin to a stinger seems to terminate the physical boundary of the object. Neither the worminess of the cord nor the presence of the stinger is accidental. Snoussi’s animal references illuminate, following Mel Y. Chen, the trans possibilities of animal genitalia. In particular, the worm’s clitellum, or smooth segment, a sexual organ that both provides and accepts sperm during intercourse, demonstrates the boundary-crossing potential of transgender, genderqueer, intersex, agender, or gender non-conforming as physical states. These conceptualizations are particularly disruptive to a Tunisian social order that prioritizes sex and gender fixity in the maintenance of the family, the society, and the state.

The mechanical-creature drawing paired with the genital-like representation is even more disorienting than its counterpart. It has very few, if any, apparent visual references that could serve to guide the viewer in identifying its components. In fact, some elements seem to reference parts of the vulval shape it faces, such as long, straight protrusions that echo the rectangles made up of parallel lines on its companion, or the folds that comprise some bodily weight in each. The merger of animal and machine enables the figure to be thought as a chimera.

There exists a potential for bodily plurality in many humans that is denied. As Chen points out “the ‘genitals’ are directly tied to social orders that are vastly more complex than systems of gender alone… Genitalia are culturally overdetermined, and, as the seats of reproduction and fecundity, they are sites of biopolitical interest not only for humans but for nonhuman animals.” Thus, in the violent gendering process, externally observable genital characteristics are in actuality being described as most like “male” or most like “female” and gender identity is “naturally” aligned with this physicality. For intersex and transgender individuals this is particularly relevant, as the illegitimacy of sex/gender systems are most apparent to people who exist outside of such organization.

As in many cultures, the sex assignment of Tunisian children based on genitalia is crucial to their existence as social subjects. The girl’s hymen is emphasized as the locus of social worth, while a boy child’s social acceptance is achieved through the highly ritualized circumcision ceremony, a celebration that can last several days. The circumcision ritual often marks the entry into male socialization. It is thus a method of gendering. The ceremony is sometimes even presented as a mock-wedding in which the boy wears bridegroom’s clothes and songs are sung about coitus. The girl’s hymen and the boy’s circumcision are components of the construction of the children as integral, gendered family members who will fulfill gendered roles within the family structure. The book of anomalies challenges hierarchies that result from meanings made within these social systems by divorcing genitals from gender and by alluding to deviant sexual relationships that derail heteropatriarchy.

In the nuclear family, gendered one-to-one relationships such as mother-daughter, manwoman, and brother-sister are prioritized. David Getsy asserts that,

Queer people are the only minority whose culture is not transmitted within the family. Indeed, the assertion of one’s queer identity often is made as a form of contradiction to familial identity. Thus, for queer people, all of the words that serve as touchstones for cultural identification – family, home, people, neighbourhood, heritage – must be recognized as constructions for and by the individual members of that community.

The importance of the heteronormative, monogamous family also aligns with sexuality. Gayle Rubin describes “a hierarchical system of sexual value” in which “marital, reproductive heterosexuals are alone at the top of the erotic pyramid. Clamoring below are unmarried monogamous heterosexuals in couples, followed by most other heterosexuals… Stable, longterm lesbian and gay male couples are verging on respectability.” Tunisian understandings of sexual hierarchy align with Rubin’s summary of modern Western societies in which the monogamous heterosexual couple is the pinnacle of sexual respectability, and differ in that premarital sex for women and homosexual sex, particularly for men, fall far below the measure of respectability. Pre-marital and homosexual sex acts performed by individuals also have ramifications for the family’s social status in Tunisia that are not always found in hegemonic Western understandings of sex.

Marriage remains critical to the social discipline of Tunisian women. Women’s rights in Tunisia may benefit women in many ways, and certainly many Tunisian woman enjoy liberties not granted to their counterparts in neighboring North African and Middle Eastern countries. However, many rights for Tunisian women given through the CPS are related to marriage and family. This structure codifies women’s rights on the conditions of marriage and within the context of heterosexual relationships. Women who are not married by age thirty, or women who are divorced, are stigmatized. Divorced women face economic repercussions as well as social ones.

As Charrad summarizes,

In a social system in which the law facilitates divorce, and where most women have no independent source of support, reliance on one’s kin group represents the main and most stable basis for security. Typically, divorced women go back to their father’s house, or… to the household of a male relative…The woman is also tied to her husband’s lineage, however, if only by the fact that her children belong to it. She is thus in an ambiguous status.

An unmarried or divorced woman is therefore a body that should be recuperated by the state for use in sexual and economic regeneration. While the state lays out the terms of women’s social existence through relationships to men and family – through marriage and children – it is society that upholds and enforces the state’s requirements. An unmarried or divorced Tunisian woman is subject to social stigma and is a cause for her family to be concerned. The unmarried or divorced woman has failed to reproduce the state in the correct manner: through the maintenance of the heterosexual, nuclear family unit. The book of anomalies problematizes heterosexual, nuclear family structure and the reproduction of such by highlighting female genitalia as active and focal, and by referencing deviant sex acts and desires.

The figures that reference genitals in The book of anomalies expose the social construction of genital biology because they demonstrate that human genitals are where human sexual difference manifests. As Pierre Bourdieu describes, “The body has its front, the site of sexual difference…It has its public parts – face, forehead, eyes moustache, mouth – noble organs of self-presentation which concentrate social identity…and its hidden or shameful private parts, which honour requires a man to conceal.” Bourdieu illuminates how genitals come to define sexual difference, as well as how sexual difference based on genitals is projected onto the “public” parts of a human. Judith Butler likewise contends that “sexual difference… is never simply a function of material differences which are not in some way both marked and formed by discursive practices.” Discursive practices help to materialize the categories of male and female, animal and human, and further divisions within each. Sexual difference is not unique to humans, as animal genitalia are also used to construct differently sexed creatures, and can also induce shame in their viewing. Yet, human genitalia are so imbued with such meanings of shame that they must be covered. An artwork such as The book of anomalies that denies genital ascription disrupts the biological fixity of sexual difference and its bodily materials by defamiliarizing categories of human, animal, and genital.

Anne Marie E. Butler.

In Unintelligible Bodies: Surrealism and Queerness in Contemporary Tunisian Women’s Art. State University of New York at Buffalo, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2019.